How to Buy Property in New York City

So, it’s come to this. You’re thinking about purchasing real estate in New York City.

Dear reader, I did this in 2023-2024. Below is a comprehensive guide on how I did this as a tech worker and transplant, after living in New York for 7 years.

Take all of this with a grain of salt. My fiancée and I are both mid-career tech workers and got to this point after each working full-time for 15+ years. Your story may not match ours, and this is not financial advice.

Step One: Are You Sure? #

Buying real estate is likely one of the biggest single financial transactions you will make in your life. Buying your “primary residence” - where you live - is a decision that involves huge financial, emotional, and logistical components. There is no one reason to buy property.

What convinced my fiancée and me, though, was that we prioritized stability above all else. For the next stage of our lives, we wanted a permanent home that we wouldn’t have to worry about being forced out of due to rent hikes, the whims of landlords, or chaos in the financial markets. The rent on our Manhattan apartment had jumped 23% the previous year, and while we realized that was an extreme outlier, we wanted to insulate ourselves from that risk as we planned our next 5-10 years.

Depending on your risk tolerance and your life plans, you may not share this reason for buying. Perhaps you want to combine your need for housing with a financial investment vehicle - that’s a valid reason to buy. Perhaps you want to stop “throwing away money” on rent; that’s fine too (although that traditional wisdom may not be accurate in NYC in 2025).

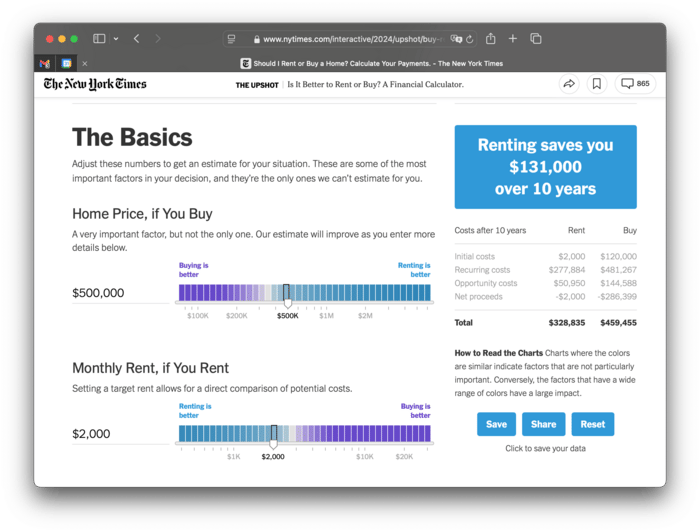

The New York Times published an excellent interactive calculator that compares renting and buying from a financial perspective. This is a great tool and an excellent place to start, although you may want to do more calculations to compare renting or buying given your particular financial situation.

I ended up doing way more spreadsheeting than this calculator (more details on that below) to determine exactly what kind of mortgage we should get, what price we could comfortably afford, and so on. The general rule that I came to strongly believe, however, was that if you know you want to live in the same NYC apartment for more than 6 years, buying makes more sense financially; even in the current high-interest-rate environment.

Where to Buy #

For the past 100 years, real estate agents have said that the top three reasons to buy a property are always “location, location, location” - and this is even more true in New York than in most other places in the U.S.

Let’s say you’ve lived in your current neighborhood for 3-4 years. You love the area, but now you want to buy property instead of renting. So, you load up Zillow, Redfin, or your app-of choice and look at listings.

And everything is way out of your budget. You’re confused, because your rent - while high - is still lower than the total monthly cost of these other units.

In NYC, it’s extremely common for an area to be relatively affordable to rent in, but extremely expensive to buy in. Why does this happen?

- Different housing stock: “Rentable” and “ownable” properties differ substantially in size, shape, and amenities. Many high-end rental buildings are owned by massive corporate landlords - with names you may recognize like Avalon, Brookfield, Two Trees - who often design their buildings specifically as rentals with relatively high turnover. Your 600-square-foot rental unit on 32nd Street may be relatively affordable, but the only properties for sale nearby are completely unaffordable 1,800-square-foot condo lofts.

- Low Turnover: rental units turn over way more quickly than sales, so opening StreetEasy to see what you can rent will paint a very different picture of a neighborhood than opening Zillow. So even if there are more affordable properties in the neighborhood, they’re much less likely to be for sale.

- Few Condo Rentals: Assuming that rental costs must be higher than ownership costs would make sense if your unit was being rented to you by a condo owner; after all, renting out a condo only makes sense the landlord can charge a premium. But in New York, the vast majority (85%+) of rental housing stock is owned by institutional landlords, rather than individuals. The assumptions fail to hold in this case; and even so, anecdotally, it can be very hard for individual landlords to rent out their units economically.

So, if you’ve become really attached to your neighborhood, and especially if you live in a big corporate-owned rental building, there’s a very good chance that you won’t be able to buy something there in your price range on the timeline you want.

Defeated by the prices you see on Zillow, you’ll start branching out. And that’s when you really need to start to explore the city a bit more.

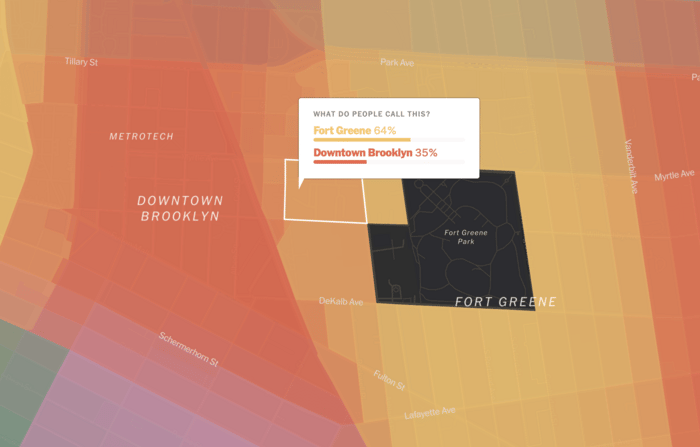

The New York Times’ Upshot published one of my all-time-favourite data visualizations in 2023: An Extremely Detailed Map of New York City Neighborhoods. This spectacularly beautiful crowd-sourced map shows neighborhoods you may have never heard of, and is invaluable to consult when a realtor assures you that a property is “definitely in Fort Greene, not Downtown Brooklyn” (they’re lying to you, they’re usually lying to you).

How, then, do you pick a neighborhood? Here’s what worked for us:

- Start by narrowing down neighborhoods by transit time. Consider how you can get to your current job, the next job you might have, areas you usually hang out in, etc.

- Make sure you’re not just off one transit line if you can avoid it; if your train line goes down for the weekend and you feel stuck at home, you’ll hate living there.

- Then, narrow down by vibes: does this neighborhood fit your lifestyle? Have you spent time here before? Do friends live in the area, or have friends lived in the area before?

- We bought in a part of Brooklyn that we had each spent enough time in to get it, but neither of us had lived in before.

- Then, narrow down based on housing stock: there will be many neighborhoods with good transit access and good vibes. Which of those have high-quality property for sale in your price range?

This worked very well for us; we chose three neighborhoods that would have been great to live in, and ended up zig-zagging across the city for viewings. (This approach can lead to some confusion with realtors, though; more on that below.)

To properly understand the vibes of an area, you probably need to spend enough time in the city to explore tons of neighborhoods and learn about each of them. As an example, friends of mine once moved to NYC from Toronto and immediately started looking to buy an apartment together. This, in no uncertain terms, was an absolutely terrible idea; not for financial reasons, but because they had just landed in the city. I asked them to name their three favourite neighbourhoods, and when they said “Yorkville and Lenox Hill” but couldn’t come up with a third. (They ended up renting and never bought.)

How to See Property #

At this point, you’ve narrowed down the city to a list of neighborhoods you’re considering buying in. Excellent. To actually see those properties, you’ll want a buyer’s agent.

I say want here because using a buyer’s agent makes the process much easier. Technically, no, you can buy a property without one. Practically, for a first-time buyer, you will find it exceedingly difficult.

A buyer’s agent will:

- Book viewings so you can see properties you’re interested in

- Suggest properties that you may not have seen, sometimes before they’re listed publicly

- Handle communication with the listing agent(s), who are selling the property

- Attend viewing with you (often to reassure the listing agent that you’re trustworthy)

- Walk you through the process of submitting an offer

- Not get paid until the deal is done

So, how do you find a buyer’s agent?

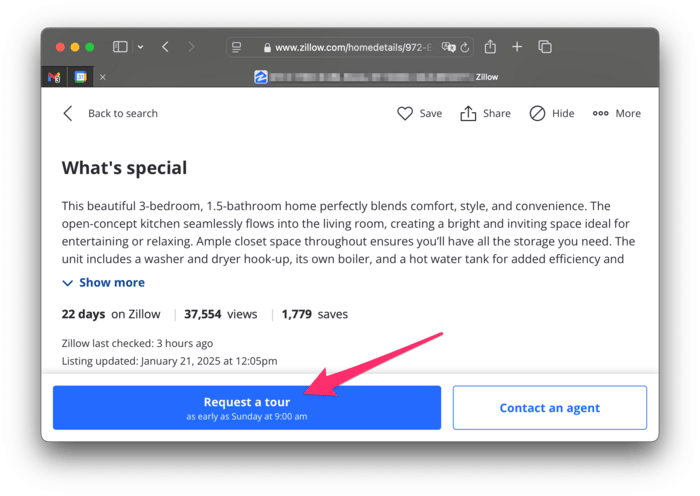

If you already have your eyes on a property, Zillow will semi-surreptitiously connect you with a buyer’s agent automatically when you click “Schedule a Viewing” on a specific property listing. A lot of effort goes on behind the scenes to choose which agent gets your business. You can work with this person, but you do not need to go through this agent.

You can, instead, find an agent on your own to represent you. You can find this agent by word-of-mouth (asking your friends, coworkers, etc) or by comparing agents you find online, etc; just like any other professional service. However, this is made more complicated by the fact that agents usually work in a specific area.

When we started looking, we used “the Zillow button” to automatically find us an agent in our area. It turns out that this agent was the same one who rented us the property, and we already had rapport with him. He made it clear that he focused on that area of Manhattan, so when we started looking in Brooklyn instead, we found a different agent entirely.

If you’re open to looking in multiple neighborhoods, you might have to find yourself an agent willing to travel outside of their usual area-of-expertise. You might even consider using multiple agents, but this can be dicey, as agents obviously don’t like having their time wasted; they don’t get paid unless you buy something they show you. This is a conversation you can have up-front, but agents do often interpret “openness to multiple non-adjacent neighborhoods” as a sign of unseriousness.

Once you have an agent; you’ll book viewings. Viewings often happen either by open house (5-6 simultaneous potential buyers in the place at once) or as dedicated, 1:1 viewings. Viewings are scheduled in advance to allow the current owners to be out of the house and to ensure the space is clean. It’s not uncommon to schedule a handful of viewings back-to-back on the same day. Before buying, we went to roughly 10 viewings.

What should you focus on during a viewing?

- Get a good look at the space, and use the fact that you’re there in person to imagine how you might fill the space.

- Take pictures and video.

- Look for potential problems up front; damage, poor maintenance, or signs of repair.

- Carefully consider how the space might look in different seasons or in different light; viewings are often scheduled at times that make the place look as good as possible. Will it still be comfortable when the sun is rising or setting? What about in the winter?

- Feel free to bring a measuring tape. (A full inspection will come later.)

When we went to viewings, I started by asking “could I live here” - which is a good question, but not quite enough, as you could live in a lot of places that aren’t optimal. I eventually switched to asking “would I like waking up here every day” and “for how long would I be happy with this place?”

If you’re buying alone, your agent will be there with you. If you’re buying as a couple, your agent will be there with you; but you should both be there. (I saw the place we ended up buying solo, by taking a good video and sending to my fiancée; we then did a second viewing days later.)

Your agent will collect some details for you, but you’ll want to ask a number of questions yourself while you’re there:

- Is the property standalone, part of a condominium, or part of a co-op?

- Is there a Homeowner’s Association (HOA)? How does the HOA work? Is there a management company? What fees do they charge?

- Is there a vent in the kitchen?

- Is there a 421-A new-build property tax abatement?

- Is there a Cooperative and Condo property tax abatement?

- What kind of heat/AC does the building have? Central? Per-unit? Window units?

- Is the building in a flood zone?

- Which appliances are included?

- How long has this been on the market?

- If the unit is a new build (i.e.: still under construction):

- Who is the developer/sponsor?

- When is the CO (Certificate of Occupancy) expected?

- When is the forecasted date for move-in?

- Is there an “outside date” (after which - if the property is not ready - the buyers can back out of the contract)

Collect answers to these questions, take your pictures and videos, say thank you to your agent, and go home.

Then do something else for an hour.

Then, revisit your photos and think critically; would I like waking up here every day? How long would I be happy living in this place?

If it’s a no, tell your agent quickly so you can pick a next property to view. If it’s a yes, move on to the next section.

Wait, What’s a Condo? What’s a Co-Op? #

In New York City, most apartments you can purchase are part of either condominiums or housing co-operatives. Both allow owning a stake of part of a larger building. Condos allow for legal ownership of your actual unit and a portion of the common areas, whereas with co-ops, you own a share of the legal entity that owns the entire building. In co-ops, you pay no property tax directly, which makes their maintenance fees appear higher, as they include your share of the building’s taxes.

Both condos and co-ops have boards, which decide who can live in the building and what rules they have to follow. Co-ops are known to be generally more strict, especially when it comes to your financial standing - some boards want to see that you have many years’ worth of maintenance payments available in cash.

Many smaller (2-5 unit) buildings in New York can also be self-managed condos, where the building is managed by the residents themselves, generally resulting in lower fees but also sometimes neglectful maintenance.

We bought in a building with a self-managed condo, which has turned out to be - for lack of a better word - “chill.” The articles of incorporation for the condo board lay out ground rules for what the group should do, but functionally, it’s an LLC, a WhatsApp group, and a Venmo account.

So, You Like A Place #

After taking some time (ideally about a day) to think about a place you’ve just viewed, you’re now interested in buying it. That’s great! Now things get tricky.

Unlike on Amazon, you can’t just click “Buy Now” on a property. Virtually all desirable properties in NYC get multiple offers shortly after their first viewing. The seller of the property has control, here: they can choose to accept any offer at any time. It’s common, however, for the listing agent to advertise a “highest and best” due date; a moment in time at which all potential buyers are asked to have their best possible offers submitted.

To submit an offer, each listing agent will often send out an offer form. These forms are usually templates given to them by their brokerage. The point of an offer form is for the seller to get some assurance that you’ll actually be able to pay for the property in some way; either in cash, or via financing (i.e.: a mortgage). You’ll be asked for your employment information, income, and an enumerated list of all assets and liabilities; how much money you’re willing to pay for the property, and how much of that you have in cash. (People call this a “down payment,” but technically it’s just “the difference between the purchase price and what you can convince a bank to lend you.”)

As part of convincing the seller that you can pay for the property, you’ll need to show proof that you can obtain financing if you don’t have the entire purchase price in cash. This is called a pre-approval letter, and is something you can accomplish in five minutes online by going to nearly any mortgage lender’s website. Technically, this lender does not matter, as you will have plenty of time to choose a better lender if your offer is accepted; sellers just want to see that a lender will lend you the remaining money, and that they’ve done their cursory due diligence on you.

For this purpose, we used Better.com, an online mortgage lender. We did not actually take a loan from Better, but they offered a completely online pre-approval process that allowed us to submit our first offer within 30 minutes of deciding to do so. This resulted in a hard credit check, which is unavoidable at this stage of the process. We were also able to change our pre-approval letter for each subsequent offer without additional hard credit pulls. (Full disclosure: many former colleagues have worked at Better. I asked them for advice on this after they no longer worked at Better.)

Your offer form will also contain a number of line items called contingencies. A contingency means what you think it means: it’s something that your offer is contingent on, meaning that your offer can only proceed if this other thing happens. Common contingencies are mortgage/financing contingencies (“can only move forward with this offer if our mortgage lender actually funds the mortgage”), inspection contingencies, or contingency on the sale of your existing property. Contingencies are not deal-breakers, but they always make your offer less competitive than other offers without contingencies.

Once you’ve filled out your offer form and you have a pre-approval letter handy, you’re ready to make an offer. You send it to your agent, who sends it through to the listing agent. You might hear back immediately, within a couple hours, or the next day, as the seller is likely considering your offer along with others. (While this happens, you should be emailing real-estate lawyers.)

In NYC, you’ll likely be competing against at least one all-cash offer. All this means is that someone else is willing to pay cash right now for the property, rather than waiting for a mortgage lender to do all the paperwork to get the funds ready. Three things you should know here:

- All-cash offers are more appealing to sellers, as they offer a guaranteed faster sale

- All-cash offers don’t technically mean that the prospective buyer doesn’t have a mortgage; they may have just taken a less-favourable loan in order to make a more favourable offer

- Competing against an all-cash offer doesn’t always mean you won’t get the property; the sellers may still like you and your offer more.

At this stage, you’ll hear one of three things from your agent:

- The seller took a higher offer

- The seller countered your offer, with either a higher price or different contingencies

- The seller took your offer

Of the five offers that we made, three were lost to higher, all-cash offers. One was countered a couple of times (which we lost) and one was countered twice (which we won).

Countering is very common; the seller, of course, wants to get the best deal possible, so you do have an opportunity to make your offer more attractive to try to win. This is often framed as a high-stakes, high-urgency decision; usually a phone call from your agent saying “we need an answer right now.”

To avoid making this a stressful negotiation, write down your absolute highest offer price on a piece of paper. Factor in everything you can - “will I be able to afford this comfortably,” “is this price reasonable given other comparable properties in the area,” etc. When your agent calls to ask if you want to increase your offer, look at the piece of paper and do not say a number bigger than what you’ve written down.

Ignore this advice if you want to; everybody has different negotiation tactics. All I know is that this strategy helped me justify my heat-of-the-moment decisions and reduced regret.

But, once you’ve done this dance of “viewing, offer, counter” enough times, you’ll eventually have an offer accepted (or stop trying). Congratulations! This is when things get complicated.

Post-Acceptance #

Having an offer accepted means that the seller intends to sign a contract of sale with you. This means five important things:

- You’ll have to engage a real estate lawyer to help you at this point

- You’ll have a lot of paperwork to read through, very quickly

- You may still negotiate over the finer points of this contract

- You’ll need to prepare to wire a deposit to the sellers, often called earnest money

- Until the contract is signed, everything could still fall through

The seller is within their rights to entertain other offers during this time; they may even accept a different offer at this time if they have any reason to think that you aren’t moving forward quickly enough with the contract.

The contract of sale is a fairly long (15-20 page) document that details how the sale will happen; who pays what to whom and when, what exactly is being sold, when the transfer of ownership takes place, and so on. Most of these details are negotiable through your lawyer, but at this stage, the purchase price and contingencies will likely be non-negotiable.

The earnest money deposit is a sign to the seller that you’re committed to making this deal go through, once signed. It’s expected that you’ll wire them this money upon signing, and in New York City, the standard amount is a staggeringly high 10% of the purchase price. (In most other places in the U.S., earnest money is only 1-3% of the purchase price.) If you sign the contract of sale and then fail to follow through with the purchase, your earnest money is forfeit. Also, in many cases, the seller will sue you in civil court for nonperformance.

Inspections #

Another crucial thing to do in this time is an inspection of the property. In especially hot markets (mid-summer in NYC, for instance) some people are bold enough to waive inspections.

DO NOT SKIMP ON INSPECTION. You are about to make one of the largest financial transactions of your life. Find the most frustratingly meticulous, thorough, and paranoid inspector you can, and hire them as soon as you’ve had your offer accepted.

Your agent will suggest that you use their inspector - they “know a guy” and have “worked with him in the past.” This inspector will be friendly, reasonably-priced, quick, and will identify things that you would have also noticed. This inspector will also “miss” anything that might cause you to back out of the deal. No, I am not being paranoid - this happened to us and cost me a ridiculous amount of stress.

If you learn one thing from this blog post, it’s that you must choose your own home inspector and they must be frustratingly thorough. Piss people off. Worry that you’re going to be told that the inspection is taking too long. Go over time. It doesn’t matter; the alternative is that you buy a property that you’ll have to repair, and that repair may cost you tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The inspector will give you a detailed report, containing photos and recommendations for repair work. This report can be used to inform amendments to the contract (i.e. “fix water damage”) that you demand before signing. If these are reasonable and backed by evidence, they will usually be agreed to. If the report contains anything to scare you away (i.e.: “compromised structural integrity” or “evidence of recurring flooding”) then you should go back to searching for properties. You will want to ask your agent if these are normal things to hear from an inspector; do not do this. They are not acting in your best interest, no matter how friendly they seem.

Okay, back to The Contract #

This period of contract review can last for roughly up to two weeks. Once you’ve decided that the inspection looks good, the contract is sound, and your lawyer agrees, you’ll sign it. This will probably happen online via DocuSign, and you’ll simultaneously wire the money to a layer’s escrow account. (This is normal; handling medium-sized amounts of money like this is part of a real estate lawyer’s job.)

This will likely be the first of many large wire transfers you need to make during this process, so get comfortable doing so with your bank. We opened a separate account just for this purpose with a bank that allows free domestic wires; doing so is not unusual, although may slightly confuse mortgage underwriters.

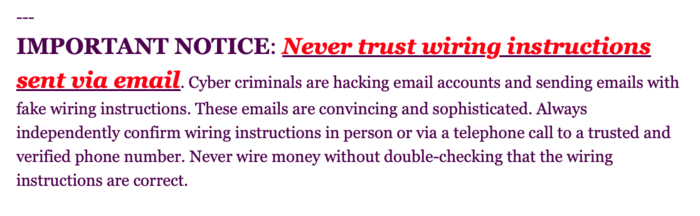

You will likely see many people send you emails that include warnings like:

This is true, wire transfer fraud is rampant in real estate transactions. The irony, however, is that some emails will ask you to call a number provided in the email to verify that the wire transfer numbers in the email are correct; providing no additional security. If you want to be extra-sure, call your lawyer on the phone using a number you’ve previously used, then get the wire details directly or get the phone number of the seller’s lawyer to call directly.

You’re “In Contract!” #

Congratulations, you’re now “in-contract” to purchase property! This has stronger guarantees than having your offer accepted, and there’s now money on the line. At this point, your primary goal until closing (i.e.: completing the transaction) is to secure the funds required to pay for the property.

For most people, this means shopping for a mortgage lender to use.

I use the word “shopping” here literally, as you are shopping for a product - a financial service, more specifically. Mortgage lenders are competing for your business, because they make most of their money up front. Even calling them lenders is not quite accurate; often, the company you get your mortgage from is a mortgage originator, who creates your loan and deals with you, the customer. Once you get a loan from them, they will usually sell that loan to another company you’ve never heard of. This is entirely normal, albeit quite confusing.

So, how do you compare different vendors when you’re buying a product for the first time and don’t really understand what they offer?

There are only two things you need to compare when considering a mortgage lender:

- What mortgage rate do they offer?

- Are they competent enough to underwrite (i.e.: perform their risk analysis, read your bank statements, communicate via email in English) your application without delaying your sale?

Some banks may have reputations for being particularly competent (or incompetent) during the underwriting process, but beyond that their “customer service” does not matter. They’re going to sell the loan to another company, and you will not deal with the bank after that happens.

Lenders offer the ability to buy “points” off of your rate - paying an additional amount up front (usually “1 point” = 1% of the purchase price) to get a reduced rate. This allows you to reduce your overall interest and monthly payment in a way that differs mathematically from just taking a smaller loan. Points can legitimately be useful; if you think interest rates are going to stay high for a while, buying a point can be cheaper than refinancing (i.e.: getting a new mortgage) later. Do your own math here. Also, note that you can write off some portion of any points you buy on your federal tax return.

We shopped around for mortgages for about a week before making a choice. We considered Better.com, Guaranteed Rate, and PNC Bank. They would have all given us very similar mortgages, and it came down to who we thought would get the job done faster. Rates were very similar for all three.

What’s a good mortgage rate? This is probably the most important question to ask. At the top of this article, I linked to an excellent New York Times calculator that helps decide if renting or buying is cheaper. But, independently, I often hear people saying things like “but a mortgage is good debt!”

Mortgages are insanely consumer-friendly financial products. The government wants people to buy property, so they let you write off a significant portion of your mortgage interest from your taxes. Mortgages in the U.S. are also phenomenal compared to other countries; in my native Canada, every mortgage is variable-rate and prepayment often incurs heavy penalties. When rates are low compared to stock market returns, taking on a mortgage is a no-brainer.

The traditional advice that “buying is always better than renting” does start to break down in a high-interest-rate environment, and especially in an expensive city like New York. At time of writing, interest rates are above 7%. That’s a higher rate than what (admittedly-conservative) Vanguard estimates can be expected in the market for 2025. When your mortgage rate is higher than your expected rate of return, the opportunity cost of owning property with a mortgage is harder to justify, and the debt - while favourable - still has very significant cost.

My own personal strategy for dealing with an expensive mortgage is to just aim to pay it off as quickly as possible to minimize the cost of servicing the loan. But again - do your own math here.

Once you’ve engaged a mortgage lender, they’ll ask for all of your documents - and this means all of your documents, like your unredacted bank statements for all accounts, prior years’ tax records, and much more. These will be used by underwriters (risk analysis employees) to decide if you’re likely to pay your mortgage. Make sure these are provided quickly and completely, and in a consistent format, to make the underwriters’ jobs as easy as possible. Even so, expect that the underwriters will not be able to read what seems like plain English.

I would not describe mortgage underwriters as “creative thinkers” by any stretch; they’re looking for keywords and specific numbers in each PDF, and will email you back with random questions that seem almost nonsensical. Just answer them quickly, clearly, and politely to get this stage over with as fast as possible.

While underwriting is happening, you’ll end up in a separate email thread with a high-touch salesperson with a title like “VP of Mortgage Lending,” who wants to lock in a rate with you. You can do so whenever you want, as mortgage rates fluctuate literally every day; depending on how long underwriting takes, you can delay this up until 4-5 days before closing if you believe interest rates will fall. Ultimately, though, this is a financial timing decision akin to picking stocks; it’s largely out of your control. Rates are usually “lockable” for 60 days, so you’ll want to lock your rate no longer than 60 days before you expect to actually close on the sale.

Your mortgage lender will also probably send an independent appraiser to the property, to make sure that it exists and that it is actually worth roughly what you’re paying for it. This will happen without your direct involvement, but you may get a copy of this appraiser’s report.

A very New York aside: the laws of the state of New York allow for buyers, sellers, and lenders of residential real estate to enter into something called a Consolidation Modification Extension Agreement, or CEMA (often pronounced “see-ma”). This sounds esoteric, but allows both the buyer and seller to save substantial amounts of money on taxes - often tens of thousands of dollars - as long as both the buyer and seller have mortgages. Functionally, you only pay mortgage recording tax on the difference between the seller’s mortgage balance and your new mortgage balance. (The seller also benefits, by paying less in real estate transfer taxes.) Note that CEMAs are not supported by all lenders, and they do add delays to the closing process; but the seller may be okay with this if they save a substantial amount too. Check with your agent and lawyer.

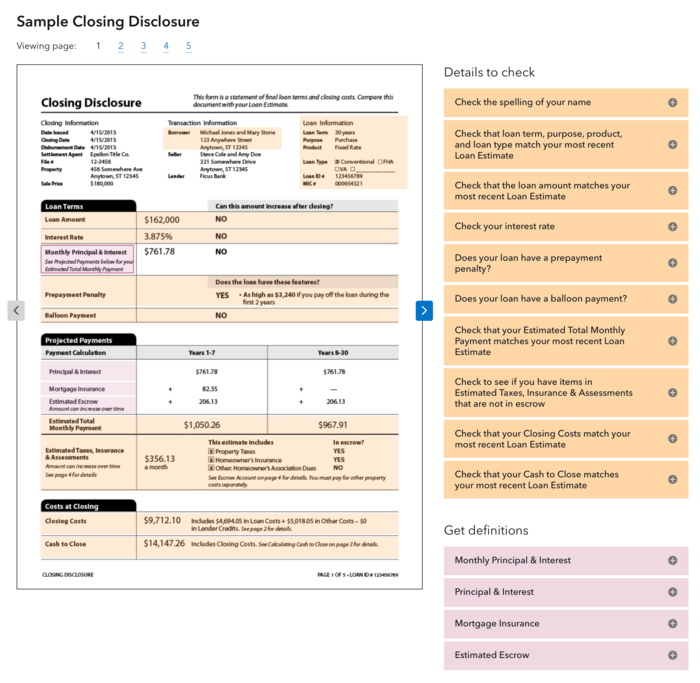

When you’re ready, you’ll probably have a quick call with your mortgage salesperson to verbally confirm that you want to lock in your rate (and optionally, how many points you want to buy). After that rate lock, you just need to wait for your lender to issue you a Closing Disclosure outlining the terms of the loan that you’re about to sign, followed by Clearance to Close, which indicates that the lender is ready to go.

Double check with your lawyer before committing to anything on the mortgage - not because your lawyer should be relied upon to prevent you from making any financial missteps, but because the timing of these commitments could be crucial.

The Closing Disclosure is a standard form that shows a lot of very crucial information, including:

- Your exact loan amount

- Your exact interest rate

- Your expected monthly payment

- If your loan has a prepayment penalty (it should not)

- Your exact closing costs

- The amount of cash (not literally bills, just in an account) that you need in order to close - which will include your down payment and all fees

You’ll notice that in your Closing Disclosure, there will be as many as 17 fees listed, with names like “Appraisal Fee” and “Title Search Fee.” You can shop for some of these if you want to, while the lender chooses the vendor for some other fees. Of particular interest might be the Title Insurance and Title Search fees, as they’re fairly high. I would recommend talking with your lawyer about finding a reputable company for these services, as the ones that we blindly used spelled my name wrong on the cover page of the mortgage documents they filed with the city. They had literally one job, and they did it incorrectly and then refused to fix it. (The inimitable Patrick McKenzie has an amazing post on the racket that society has agreed to call “the title insurance industry.”)

Closing #

Closing on a real estate transaction is maybe the only time you’ll meet most of the parties involved. Closing is, effectively, an in-person meeting of 5-6 parties (buyer, seller, lawyers, lenders, vendors, etc) in which dozens of documents are physically passed around for signing.

To be ready to close, you need all parties to agree on the date, and you’ll need each party to be prepared. If you have a good lawyer, they should handle most of this for you. You just need to show up to a lawyer’s office and sign a lot of stuff.

Closing is also when your down payment is required in full; you’ll wire it to the seller’s attorney’s escrow account, or via your lawyer.

Closing will feel like a barrage of confusing paperwork that - initially - you understand and recognize, and by the end, you sign without thinking too hard about it.

And then you get the keys.

But wait, what could go wrong? #

So many things can go wrong in this process. A couple things that happened to us, but which I left out of the many paragraphs above for expediency:

- Between our loan’s underwriting and the conclusion of our CEMA, our lawyer helpfully explained that the unit we were buying had dozens of outstanding violations on file with the New York City Office of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). These violations predated the building’s gut-renovation, and were all obsolete, but their presence on the metaphorical books at City Hall would have caused us real and substantial fines at some point in the future. Getting these corrected required asking the condo board to hire a third-party HPD violation removal company as a contingency of the sale.

- Our closing was delayed by many hours while waiting for a crucial document to be sent via courier from a lawyer’s office. We (shockingly) went home before we were “fully closed” because this document had been seemingly lost in transit, and we were called back multiple weeks later to sign that document.

And what could go wrong afterwards? #

After we moved in:

- Many problems not identified by our inspector - which later had obvious signs - cost us more than $30,000 in repairs, and took more than 6 months to fix. Get your own inspector and make sure your inspector is frustratingly thorough.

- The gas-powered clothes dryer caught fire due to years of lint build-up in the back of the unit, requiring complete replacement (and a mild panic throughout the building). Luckily, there was no damage to anything but the dryer.

- The building’s fire alarm control panel didn’t work. The condo board had never tested it. It worked so well, in fact, that it got the fire department to show up within 2 minutes after the smoke detector in the basement was accidentally set off by repair work (and the “cancel” button on the control panel didn’t work).

- I started receiving a ton of physical mail spam related to the purchase. Only afterwards did I realize that any and all real estate purchases in New York City are publicly visible on ACRIS, including mortgage documentation and deeds containing plenty of personal information. (There is a way to avoid this public disclosure, by registering your ownership via an LLC; unfortunately, doing so in New York City makes you ineligible for certain tax credits. I preferred the tax credits.)

- The building’s front staircase was found to be a great hiding spot for local vagrants. (I installed a motion-activated siren and camera, and they have not been back.)

- Local graffiti artists took a liking to the front planter. Home Depot sells graffiti remover for $14.97.

Was it worth it? #

More than a year after buying property in New York City, I can confidently say: I don’t know if it was worth doing so. But that’s to be expected, as our reasons for buying were about long-term stability; having space to grow without worrying about rent hikes. So far, we’ve invested roughly 2% of the purchase price in a combination of repairs, improvements, and modernizations; and while we expect that number to be slightly lower next year, spending 1-2% of the property value per year would not be unexpected. The true value of most home purchases only becomes evident in year 3, 4, or 5.

But overall, buying should not be strictly a financial move. Buying property in any city - but especially New York - is a hedge against risk. I now have a reliable home base for us to use to start the rest of our lives in. And that’s worth all of the hassle. (Or, at least that’s what I tell myself.)

Special thanks to Lynn Root, Zameer Manji, Matt Levin, Alessia Bellisario, and Gillian Lau for reviewing drafts of this post.