The Ubiquitous Capture Device

Every so often, I find myself in a camera store, gawking at beautiful, expensive cameras and lenses. DSLRs have dropped in price, and mirrorless interchangeable lens cameras (also known as micro four thirds) now fill the gap between cheap point-and-shoot and semi-pro. However, every single time I go to make such a purchase, I stop myself.

It’s not that I don’t want a good camera, it’s that I already have a camera good enough. Most of us have one on us at all times.

It’s my smartphone, and it can capture images like this:

This image isn’t pristine. It’s vibrant, although it could be moreso. It’s lacking in detail, a bit noisy, and somewhat compressed. (Compressing it for web didn’t help with the presentation, either.) However, none of that is important. It’s a beautiful reminder of that moment - a great lunch with a great person, on a bright and sunny day, in a crowded restaurant. Having that moment captured is vastly more valuable than the quality of the image.

It’s true that my smartphone doesn’t take beautiful 18MP stills, nor does it

have an immaculate 10x optical zoom. The lens isn’t removable, nor is the sensor very large. Low-light performance is horrible. The built in HDR mode, while better than nothing, often produces horrible artifacts and delays my next shot for seconds. I have no control over aperture, ISO, shutter speed or white balance.

Most of this doesn’t matter though, as my phone is always in my pocket. What I lose in image quality and configurability, I gain in ubiquity. I might forget to grab my camera before I leave the house - and I’ll definitely have to think twice about bringing a huge DSLR along. But my phone? The only places I might not bring it are the shower and the swimming pool. I certainly use my camera enough, now that I’ve found an interesting use for lots of low-quality smartphone photos.

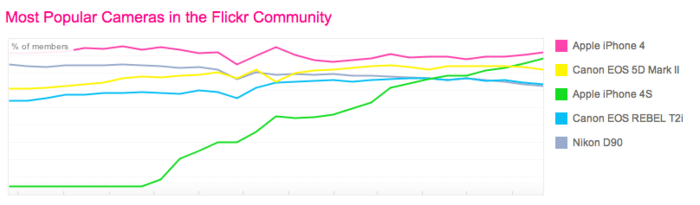

Apple’s iPhones 4 and 4S are now the two most popular cameras on Flickr.

Interestingly, people often embrace the lack of quality in smartphone photos. Photo filters are all the rage. When beautiful photo quality can’t be achieved, people delight in reducing quality even further by adding artistic emotion with a filter. (Ostensibly, most Instagram users don’t think that deeply about the filter they choose.) Instead of creating art via careful manipulation of a fancy camera, people do it with a one-touch filter.

Extending the idea to another medium, smartphones often have adequate

microphones. As a musician with a penchant for experiments in audio, I do a lot of recording. I nearly bought an expensive Zoom field recorder recently, only to stop myself again in favour of my phone’s more-than-adequate microphones. To capture musical ideas or field recordings, it’s perfect for the same reason - my phone is always with me, and is good enough.

Most of my recent songs are built around samples taken with my iPhone. “Train In The Sky” takes its snare sample from the closing of a Vancouver

SkyTrain’s doors. “Mace and Anvil” takes part of its melody from the same train’s public alert sounds. “Somnambulist” (below) starts with samples (albeit, altered samples) of myself walking, and is filled with the enthusiastic cries of the chefs at a Japanese restaurant. All of these samples, while relatively low-quality, were taken with my phone.

As Chase Jarvis puts it, “the best camera is the one that’s with you.” The

ability to capture any moment at any time, no matter the quality level, is key.

For all I care, my pictures and sounds could come out as a grainy, hazy mess. As long as I can extract meaning and value from them, I’ve captured a moment and strengthened a memory.